The German General Who Thanked Patton — And Told Him a Truth America Wouldn’t Accept

In the final months of World War II, as Nazi Germany collapsed under sustained Allied pressure, thousands of German officers were taken into custody. Among them were experienced generals, men who had fought on multiple fronts and who understood modern warfare with a depth few civilians could fully comprehend. These were professional soldiers confronting the consequences of total defeat, observing with clarity the forces that had overwhelmed them.

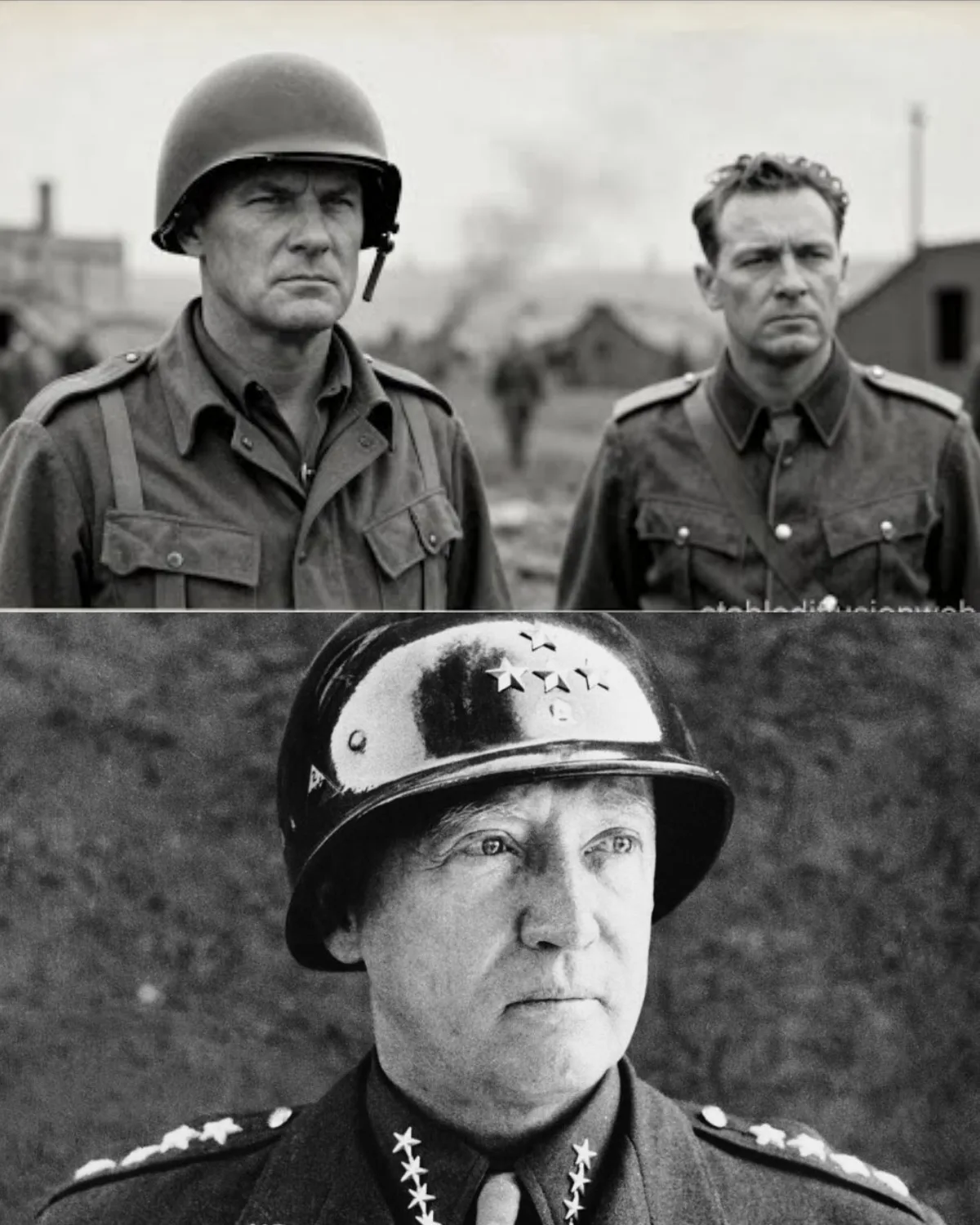

One of these generals would later make an unexpected statement about an American commander, a judgment that never became widely accepted in the United States. The commander in question was General George S. Patton. Patton was feared by the enemy, criticized at home, and frequently misunderstood by the public. While the American narrative of victory often emphasized industrial output and air superiority, many German officers quietly credited something else on the battlefield: speed, aggression, and relentless pressure. They associated all 3 qualities with Patton.

By early 1945, the German Army was no longer capable of winning the war. Its strategic position was irretrievable, its resources depleted, and its lines collapsing. Yet its officers remained professionals, trained to assess military capability without illusion. When captured by American forces, many were surprised by the manner in which they were treated, particularly in areas where Patton held command. Patton believed that professional soldiers, even those of an enemy army, deserved respect. He openly stated that wars were fought between armies, not between individual soldiers. This perspective left a strong impression on German officers who had expected humiliation but instead encountered discipline and order.

During postwar interrogations and in later memoirs, several German generals described Patton as the most dangerous American commander they faced in the Western theater. Their assessment was not based on the size of his forces. It was rooted in his conduct of operations. Patton did not wait for perfect conditions. He did not delay for comfort, and he did not fight defensively unless compelled to do so. German intelligence services repeatedly misjudged his movements. When they expected him to consolidate his gains, he attacked. When they assumed that weather or terrain would slow operations, he accelerated them.

This pattern became unmistakable during the aftermath of the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944. German forces launched a surprise offensive that broke through American lines, surrounding the town of Bastogne. Many Allied commanders believed that relieving the encircled forces would require weeks. Patton accomplished it in days. He redirected the Third Army nearly 90° in harsh winter conditions, executing a maneuver that many German officers later admitted they had considered impossible at such scale and speed.

The relief of Bastogne became emblematic of Patton’s method of war. It demonstrated not only operational flexibility but also the decisive speed that defined his command. After the war, a captured German general reportedly told Patton that his greatest weapon had not been his tanks or his artillery. It had been his ability to make decisions without hesitation. In modern mechanized warfare, where momentum often determined survival, that quality proved decisive.

The same general acknowledged something more unsettling for American audiences. He suggested that Patton was often restrained, criticized, or politically isolated not because he lacked effectiveness, but because he did not conform to the image of a hero that America preferred. Patton was blunt in speech and direct in manner. He was openly aggressive. He spoke without filters and showed little patience for diplomatic restraint. In peacetime politics, such traits made him a liability. On the battlefield, they made him formidable.

German commanders did not fear Patton’s temperament as a matter of personality. They feared what it produced operationally. His unpredictability disrupted their planning cycles. His refusal to conduct slow, methodical advances denied them time to reorganize defensive lines. Even when German forces retained the capability to mount resistance, his constant pressure forced them into retreat. He imposed upon them a tempo they struggled to match.

From the perspective of these defeated officers, the conclusion was straightforward. Patton shortened the war in his sector by refusing to wage it cautiously. This judgment was not an expression of admiration. It was professional recognition. These men had no incentive to flatter their enemy. They were offering an assessment grounded in their own experience of fighting him. They evaluated effectiveness as soldiers, and by that measure, Patton stood apart.

Yet this interpretation never fully entered American public memory. The narrative of victory in the United States centered on broader themes: industrial might, coalition strength, and technological superiority. Patton’s style, abrasive and unapologetic, did not easily fit within a unifying national story that preferred restrained heroism and institutional success over individual ferocity.

After the war, Patton became a controversial figure. His public statements, his temperament, and his political views increasingly overshadowed the operational brilliance he had demonstrated during the conflict. His outspokenness created friction at a moment when diplomacy and reconstruction required careful language. In the emerging political climate of the postwar period, his manner seemed ill-suited to the new realities of occupation and international balance.

He died only months after victory, before time and distance could bring greater balance to the judgment of his career. The debate over his character continued, often focusing more on his personality than on his battlefield record. In public discourse, complexity gave way to simplification, and his image hardened into either admiration or criticism.

Germany’s generals, however, expressed a more restrained conclusion. They did not describe Patton as kind, nor did they claim he was flawless. They did not romanticize him. Their assessment was narrower and more precise. They described him as effective. In war, effectiveness is the measure that carries the greatest weight.

Sometimes the most candid evaluation of a commander does not come from allies, politicians, or newspapers, but from the enemy compelled to confront him in battle. That was the acknowledgment made by a German general who had faced Patton’s advance and survived to reflect upon it. It was a recognition grounded not in sentiment but in professional judgment. It was also a truth that the United States, in shaping its collective memory of the war, never fully embraced.