When Heated Rivalry returns for Season 2, many viewers expect the tension to escalate. After all, the first season transformed Ilya Rozanov and Shane Hollander from on-ice enemies into secret lovers navigating eight years of longing, denial, and impossible timing. But as details about the sophomore installment — based on Rachel Reid’s The Long Game — continue to surface, one thing is becoming clear: the central conflict won’t revolve around a single mustache-twirling antagonist.

The true villain of Season 2 isn’t just a man. It’s a system.

On the surface, there is an obvious candidate. Commissioner Roger Cromwell, a powerful league authority figure in the source material, embodies institutional indifference. He turns a blind eye to toxic locker room culture and allegedly pressures players to maintain a carefully controlled public image. When he learns about Shane and Ilya’s relationship, his reaction is not protective or progressive. It is strategic. Cold. Threatening. If the show closely follows the novel, Cromwell will undoubtedly be painted as a formidable obstacle.

But focusing solely on him misses the larger picture.

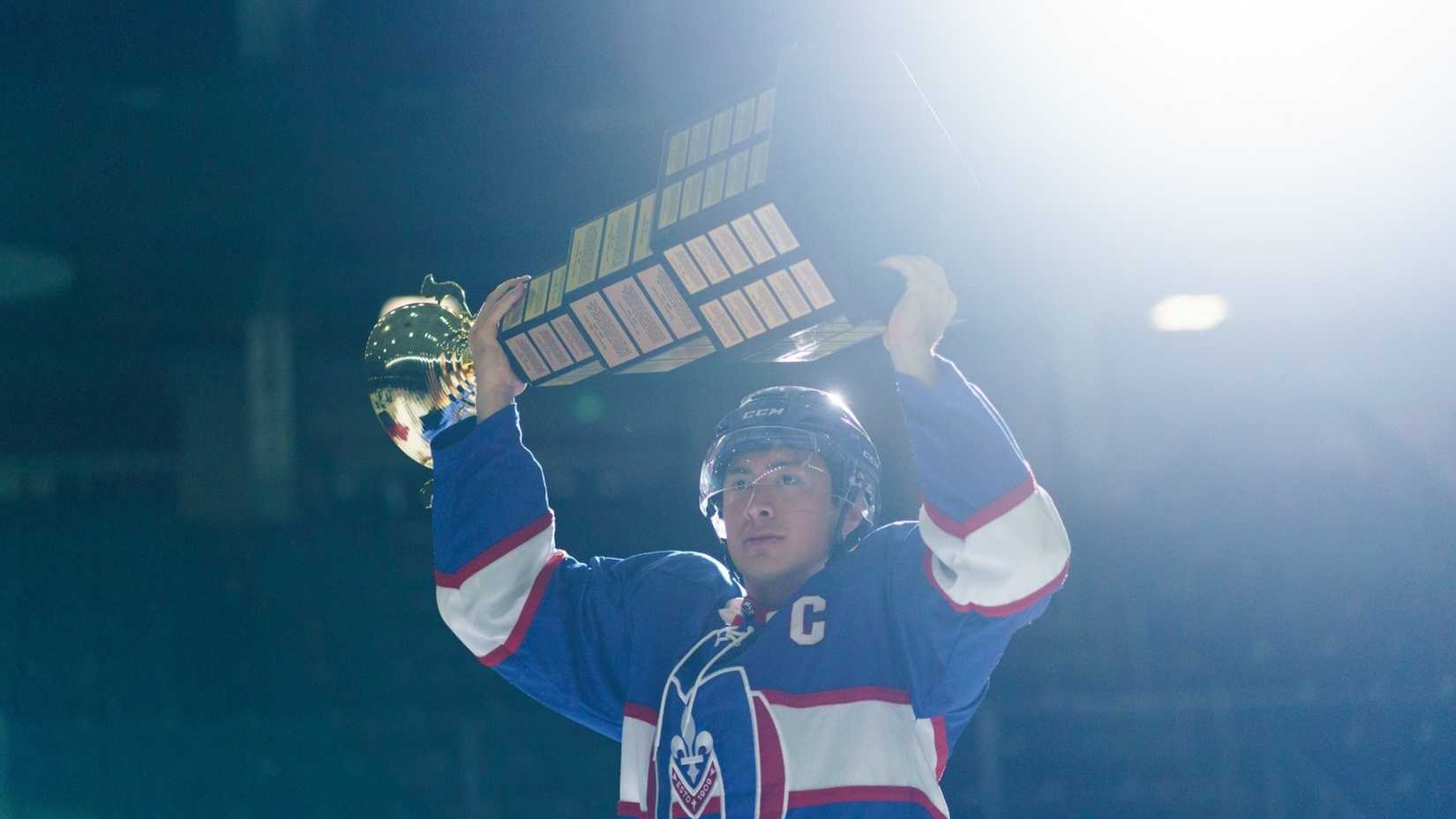

Readers of The Long Game know that the deeper betrayal comes from within Shane’s own organization: the Montreal Metros. The team he captains. The franchise he gives everything to. The crest he wears over his heart. After Shane makes the courageous decision to come out to his teammates, what follows is not the triumphant solidarity arc many sports dramas might offer. Instead, it’s complicated. Uneven. Painfully realistic.

Some teammates struggle. Others remain silent. The organization prioritizes optics. The support Shane deserves feels conditional at best.

“It’s not that there’s one villain,” one fan wrote on a discussion board. “It’s that the room goes quiet.” That silence — heavy and calculated — becomes more damaging than any overt hostility. In a league built on hyper-masculinity, tradition, and unspoken codes, neutrality can feel like abandonment.

Season 1 of Heated Rivalry, originally developed by Crave before being picked up by HBO Max, thrived because it humanized its leads. Ilya’s bravado masked vulnerability. Shane’s composure concealed longing. The show excelled at portraying internal conflict. Season 2, however, shifts that tension outward. The relationship may be stronger, but the world around them becomes harsher.

What makes this storyline especially compelling is its refusal to simplify the stakes. There is no single locker room bully positioned as the embodiment of evil. Instead, the threat emerges from culture itself — from institutional inertia, from corporate image management, from teammates who are “not against” Shane but not fully with him either. It’s a far more unsettling antagonist because it feels plausible.

Sports history has shown how rare openly gay male athletes remain in major professional leagues. The fear of backlash, endorsement loss, and team disruption is real. By centering Season 2 on that systemic pressure, Heated Rivalry moves beyond romance and into social commentary.

Some viewers have already expressed anxiety about how faithfully the show will adapt these elements. The novel is denser than the first book, packed with heavier themes and a broader ensemble of side characters. Time constraints could force creative condensation. “I just hope they don’t soften it,” one reader commented online. “The point is that it’s messy.” That concern reflects how deeply audiences have invested in authenticity.

If handled with the same nuance as Season 1, the Montreal Metros’ response to Shane’s coming out could become one of the most emotionally charged arcs of the series. The betrayal is not explosive; it’s gradual. It’s the difference between public statements and private behavior. Between press conferences and locker room conversations. Between a rainbow-themed social media post and genuine allyship.

And that’s where the brilliance lies. By framing the team — not as cartoon villains, but as representatives of entrenched culture — the show underscores a painful truth: harm often comes from systems designed to protect themselves.

Ilya, in contrast, becomes Shane’s fiercest defender. Their relationship, once defined by secrecy, is forced into the open. The irony is sharp. For years, the greatest threat to their love was exposure. Now, exposure becomes the catalyst for confronting an environment that never made space for them in the first place.

“It’s going to make people uncomfortable,” another fan predicted. “But that’s why it matters.” Discomfort signals growth. It challenges viewers who may have assumed that talent and leadership alone guarantee acceptance. Shane is not a fringe player; he is a captain. If even he faces institutional hesitation, what does that say about everyone else?

Season 2’s antagonist, then, is layered. Yes, there may be a commissioner who embodies bureaucratic resistance. Yes, there will be individuals who falter under pressure. But the real adversary is collective — a culture slow to evolve, clinging to outdated notions of masculinity.

That revelation shifts expectations entirely. Instead of waiting for a showdown between hero and villain, audiences are preparing for something subtler and perhaps more infuriating: watching good people fail to be brave enough.

And in that sense, the show’s boldest move may not be identifying a villain at all. It’s showing that sometimes, the most despicable force isn’t a single face.

It’s the room that refuses to stand up.